What is this research project about?

WiSP in Numbers

Writing in professional social work practice in a changing communicative landscape (WiSP) in our original research phase

- Liaison with 5 Local Authorities

- 81 transcribed interviews with 71 social workers in children’s, adults and mental health services

- Writing activity logs in 3 Local Authorities

- 10 weeks of observation and field notes

- 1 million word corpus of written texts

- 42 text histories featuring cases in detail

To read more on the progress, issues and challenges faced, take a look at the ‘project news and updates’ page.

A day in the life of a social worker.

To get an idea, take a look at A Day in the Life of a Social Worker, by Barry Cooper and Rai. Have a look for when and where writing happens (you should notice typing at desktop, note making in a book, completing electronic forms..)

How are we researching?

The overall aim of the Wisp Project original research phase was to build a rich picture of what it means to write and record in contemporary social work practice.

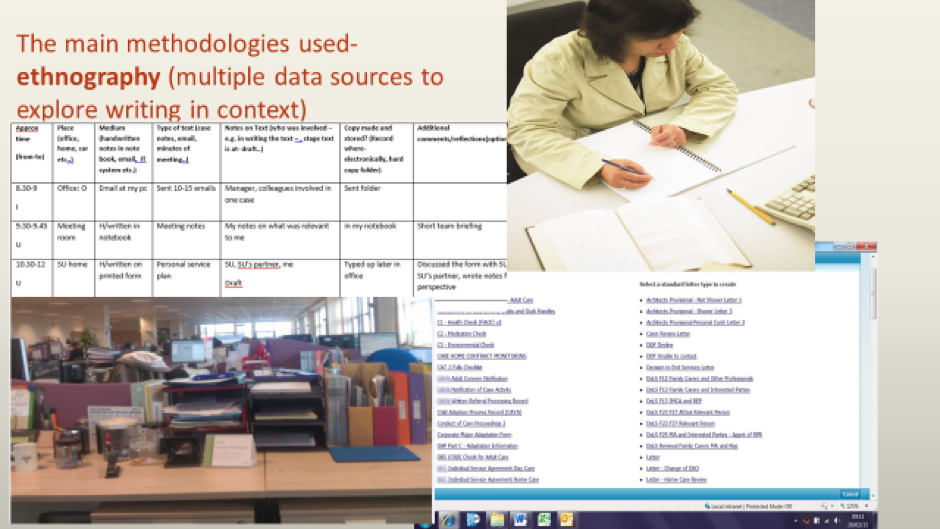

To do that we are using a combination of ethnographic and corpus methodologies in approaching data collection and analysis.

The particular ethnographic methodology we are using is what we call a ‘text-oriented ethnographic’ approach. This approach focuses on individual social workers and their text production, whilst taking into account immediate contexts of production as well as institutional practices shaping such contexts.

A key aspect of the project involves building a corpus of 1 million words of professional social work writing. The corpus will include the range of social work texts as well as a substantial subcorpora of a key writing practice in all social work domains, case notes.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves collecting a wide range of data to try and build as rich a picture as possible about a particular phenomenon – in this case ‘writing’ in everyday social work practice.

We used different approaches to collect data about everyday writing practices. The overall ethnographic approach adopted in this project means that we are interested in exploring writing in context – asking questions like:

- when is writing happening?

- where is it happening?

- why is it happening?

- who’s involved?

- what else is happening at the same time?

In the WiSP project we used interviews, researcher observation, social worker logs as well as collecting a large number of texts (from text messages to diary entries, 20-word emails to 20-page reports) to explore where and how writing fits in the day-to-day practice of social work.

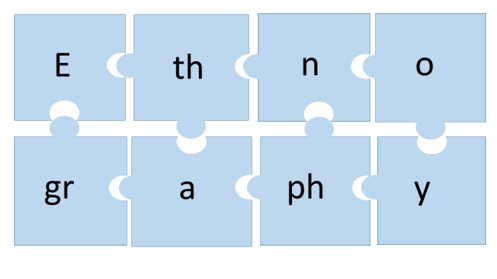

Putting data from all of these together enabled us to build a detailed and contextualised picture of how writing fits within social work in action, and any solutions or challenges they may face, using participants’ own perspectives on their experiences. Building a rich picture is rather like a jigsaw when it’s finished.

Putting data from all of these together enabled us to build a detailed and contextualised picture of how writing fits within social work in action, and any solutions or challenges they may face, using participants’ own perspectives on their experiences. Building a rich picture is rather like a jigsaw when it’s finished.

Corpus linguistics

The WiSP project team have compiled a collection of 1 million words of texts written by social workers.

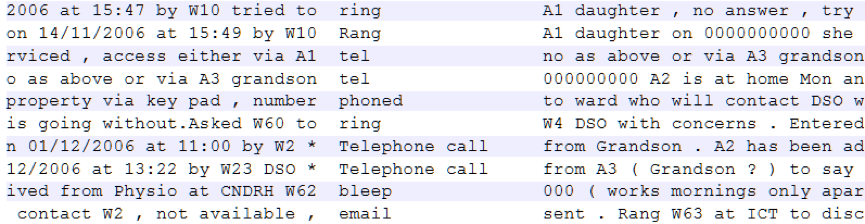

One way of analysing this electronically-stored collection of texts (or ‘corpus’) is through computer software using the methodology of corpus linguistics. Here, we show the kinds of analysis that can be carried out and what this reveals. For this example, we used a relatively small corpus of 18,000 words of case notes around one individual service user. The service user is an elderly woman who is visited daily by carers. All names of individuals have been removed so that the corpus is fully anonymised.

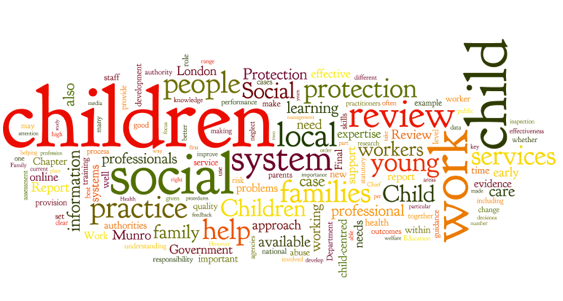

To give an overview of the small corpus of case notes, we first ran it through a wordle programme. Small, function words such as the, a, in on aren’t included in the wordle as otherwise they would dominate.

Unsurprisingly, home, staff and services feature heavily as the context is carer visits. In this set of case notes, the individual concerned had problems with her left foot, so there is high use of words such as wheelchair, leg, left, physio.

Unsurprisingly, home, staff and services feature heavily as the context is carer visits. In this set of case notes, the individual concerned had problems with her left foot, so there is high use of words such as wheelchair, leg, left, physio.

Using computer software, we then ran the corpus through a tagging programme called Wmatrix to assign grammatical tags – or labels – for each word. For example, ‘I’ is an example of a pronoun and is tagged ‘PPIS1’. This allowed us to compare the types of words in the corpus to those in a larger corpus. We compared the grammatical words in the example case notes to the 80,000 word written BNC (British National Corpus: http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/).

Here’s what we found:

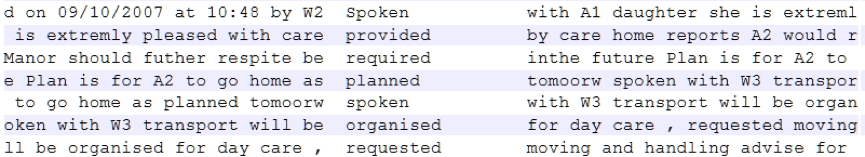

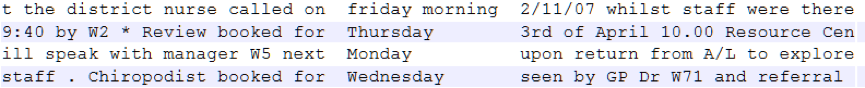

1) The case notes have many more instances of verbs in the past tense e.g. placed, knocked, spoken, advised, organised. The examples below show some of these words in context.

The use of these words shows how the case notes are written in the past tense and in an abbreviated way. In the top line, we’re not told who spoke with the service user’s daughter – this is assumed to be the report writer and doesn’t need to be stated.

The use of these words shows how the case notes are written in the past tense and in an abbreviated way. In the top line, we’re not told who spoke with the service user’s daughter – this is assumed to be the report writer and doesn’t need to be stated.

2.There are lots of verbs in the infinitive e.g. ‘to give, to phone’. Again, this is due to the abbreviated report style of the writing. Carers are writing quickly, giving the key information.

3.There are few instances of ‘I’

4.The report contains frequent mentions of times and days of the week e.g.

We also compared the example case notes with the British National Corpus in terms of the words grouped by meaning. This highlighted the extensive communication reported in the case notes. Carers often report on who they emailed or phoned in order to record that they have organised further care and generally kept everyone informed.

So what…

How can corpus searches help us understand writing in social work?

The brief examples here are from a fairly small corpus of case notes from just one service user (18,000 words). But already, it tells us something about the patterns of such writing – the abbreviated way in which the notes are written up, the focus on arrangements (times and days in the future) and the extensive reporting of what has been done and on who has been informed.

With a larger set of social work texts – the full WiSP corpus of 1 million words – we can say a lot more about the different styles of writing and about writing in different text types. Overall, this helps us to document key patterns in the different types of writing and to discuss with social workers their views on the extent to which such writing is appropriate and useful. Findings and insights generated can feed into discussions around who writes what and why, and be used in social work education and training.

The WiSP team are very grateful to Signe Oksefjell Ebeling at Oslo University for expert advice on corpus compilation and anonymisation. Our thanks also to Pete Whitelock who worked as a consultant on text anonymisation.

Moving into a new phase in 2022

We are now building on the WiSP research, taking it into a new impact phase. Through renewing partnerships with service users, educators, social workers, managers and policy makers the findings will be used to transform social work writing and inform practice across the UK nations.

This exciting new phase of work is being led by Lucy Rai who chaired the WiSP Advisory Group during the original research. This group (with representation from service user, social work educators, social workers and managers, trainers, professional bodies, Unison and the HEA) provided stakeholder insights throughout the research phase.

Our impact phase will involve experts by experience at the heart of exploring our partnership approach, analysis of existing resources and generating new learning materials for social work practice.

Watch this our project news and updates for more information and opportunities to get involved in this work.